The Paintings of James McNeill Whistler

YMSM 139

Blue and Silver: Screen, with Old Battersea Bridge

Date

Blue and Silver: Screen, with Old Battersea Bridge dates from between 1871 and 1873. 1

1866-1870: The screen incorporates paintings by Nanpo Jyoshi (Osawa Nampo, b. 1845) that are signed and dated 1866 and 1867, and were sent to Europe before 1871. They are now on the verso of the screen, but it is not known when these paintings and Whistler's work, which are on separate supports, were framed back to back and made into a screen.

1871: Whistler's painting is dominated by the piers of old Battersea Bridge, but the Albert Suspension Bridge is shown under construction in the background. Building on that bridge started in May 1871. According to The Times of 23 August, 'a timber staging resting upon piling across the river from shore to shore was completed and opened on Monday'. 2

The new Albert Bridge, seen through old Battersea Bridge, pastel, The Hunterian

Whistler's related drawings, including The new Albert Bridge, seen through old Battersea Bridge m0480, depict the preliminary timber superstructure of the two central pairs of towers, showing that the composition of the screen was planned in the summer of 1871.

1872: Whistler wrote in December to Charles William Deschamps (1848-1908), 'I am finishing a screen that I will only have this chance of showing you - and I have an idea that "something is to be done" - about which we might "dodge a means" - etc. - ! However come and see.' 3 By this he presumably meant that the screen could be exhibited, and perhaps in money or commissions.

1873: The Albert Suspension Bridge was completed.

Whistler, Blue and Silver: Screen, with Old Battersea Bridge, The Hunterian

1874: The screen was exhibited in Mr Whistler's Exhibition, Flemish Gallery, 48 Pall Mall, London, 1874 as 'Screen – Blue and Silver'.

Images

Whistler, Blue and Silver: Screen, with Old Battersea Bridge, The Hunterian

Whistler, Blue and Silver: Screen, with Old Battersea Bridge, photograph, 1980

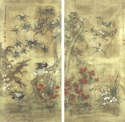

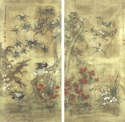

Nanpo Jyoshi, Birds and Blossoms, Autumn, verso of screen, The Hunterian

Nanpo Jyoshi, Birds and Blossoms, Autumn, verso of screen, photograph, 1980

J. Hedderly, Looking west towards ... Battersea Bridge, 1870/1875, photograph, Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea Libraries

Whistler, The new Albert Bridge, seen through old Battersea Bridge, The Hunterian

Whistler, A span of old Battersea Bridge, The Cecil Higgins Art Gallery,

Bedford

Whistler, Old Battersea Bridge, Private Collection

Whistler, Study for 'Blue and Silver: Screen, with Old Battersea Bridge',

Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo

Whistler, Nocturne: Battersea Bridge, Freer Gallery of Art

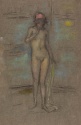

Whistler, A nude girl in front of a screen, The Hunterian

M. Dornac, Whistler at 86 rue Notre Dame des Champs, photograph, 1890s, Freer Gallery of Art

Whistler, Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Little Blue Girl, Freer Gallery of

Art

Subject

Titles

Minor variations on the title are as follows:

- 'Screen – Blue and Silver' (1874, Flemish Gallery). 4

- 'Blue and Silver: Screen, with Old Battersea Bridge' (1980, YMSM). 5

The 1980 title 'Blue and Silver: Screen, with Old Battersea Bridge' combines Whistler's original title with a site specific reference, and has become the accepted title.

Description

A screen with two vertical panels; when fully open the screen is nearly square.

Whistler, Blue and Silver: Screen, with Old Battersea Bridge, The Hunterian

Recto by James McNeill Whistler: on the right side of the left-hand panel is a timber pier of Old Battersea Bridge, and one of its massive wooden piles extends onto the right panel. The roadway of the bridge runs across near the top, curving slightly down to right, and cutting across the top of a golden moon. Seen under the arch of the bridge at left, on the river bank is a church tower with golden clockface, reflected in the water, and at right are the scaffolding and timbers of another bridge, and, beyond that, buildings on the river bank fading into the distance.

Nanpo Jyoshi, Birds and Blossoms, Autumn, The Hunterian

Verso by Nanpo Jyoshi (Osawa Nampo, b. 1845): oil and watercolour on silk, signed and inscribed in Chinese characters on the right screen, 'This work was painted near Meirindo by Nampo in third period of ten days of July 1867', and on the left screen, 'This work was painted near Meirindo by Nampo in first period of ten days of August 1866.' Originally part of a larger screen, these panels, by the Japanese woman artist Nanpo Jhoshi, were painted with doves, flowering shrubs, and plants in a Chinese style.

Site

Whistler's screen shows a nocturnal view of the Thames from upstream, with a pier of Old Battersea Bridge in the centre, and beyond it, the clock tower of Chelsea Church on the panel at left, and the Albert Suspension Bridge in the far distance on the panel at right.

Whistler, The new Albert Bridge, seen through old Battersea Bridge, The Hunterian

The Albert Suspension Bridge was then under construction, as seen in Whistler's drawing, The new Albert Bridge, seen through old Battersea Bridge m0480, reproduced above.

According to The Times of 23 August 1871, 'a timber staging resting upon piling across the river from shore to shore was completed and opened on Monday', and on 20 October it described 'the largest cylindrical iron castings ever made' as the being 'in the course of erection', to support four sets of towers for the bridge. 6

J. Hedderly, Looking west towards ... Battersea Bridge , photograph, Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea Libraries

Photographs by Whistler's friend, James Hedderly (ca 1815-d.1885), show Battersea Bridge in the mid-1870s. 7

Comments

The Hunterian website commented:

'This important work strikingly combines Whistler's interests in night-time views, the Thames, the decorative arts, and the art of the Far East. ... The format of a decorated folding screen derives directly from oriental models. Whistler has been credited with being the first western screen-maker to experiment with the concept of a folding image.' 8

A development of the composition of the screen is seen in the slightly later Nocturne: Blue and Gold - Old Battersea Bridge y140.

A nude girl in front of a screen, The Hunterian

Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Little Blue Girl, Freer Gallery of Art

The screen is also seen in the background of a pastel, r.: A nude girl in front of a screen; v.: Illegible m1388, and in Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Little Blue Girl y421, which was probably started in Paris in 1893/1894 but on which Whistler continued to work for some years.

Technique

Composition

Whistler, Blue and Silver: Screen, with Old Battersea Bridge, The Hunterian

Whistler, A span of old Battersea Bridge, The Cecil Higgins Art Gallery,

Bedford

Whistler, Study for 'Blue and Silver: Screen, with Old Battersea Bridge',

Albright-Knox Art Gallery

The composition of the screen is closely related to the actual appearance of the site, with Old Battersea Bridge in the foreground and the new Albert Bridge behind. Several preliminary drawings, which are bisected down the middle like the screen, clearly show the Albert Bridge under construction (A span of old Battersea Bridge m0481, Old Battersea Bridge m0482, and the drawing on the recto of another sheet of brown paper, r.: Study for 'Blue and Silver: Screen, with Old Battersea Bridge'; v.: Seated nude, man in top hat; figure, buildings m0483).

The new Albert Bridge, seen through old Battersea Bridge, The Hunterian

Nocturne: Battersea Bridge, Freer Gallery of Art

Related drawings include The new Albert Bridge, seen through old Battersea Bridge m0480, and a richly coloured pastel, r.: Nocturne: Battersea Bridge; v.: Standing Female Nude m0484. It is not clear at what stage this vivid pastel was drawn.

Technique

Whistler, Blue and Silver: Screen, with Old Battersea Bridge, The Hunterian

The composition was painted on brown paper laid on canvas, which has been stretched on the back of silk with a painted design of flowers. The side painted by Whistler was examined closely and investigated technically by Dr Erma Hermens and Dr Joyce H. Townsend in the late 1990s. 9 Professor Townsend carried out materials analysis then and later: her analysis follows:

'The reddish-brown paper support was utilised as the ground colour. Whistler executed many pastels on brown paper which was often mid-toned. The screen’s support is today noticeably dark in comparison. Whistler’s technique for the screen greatly resembles that used for his pastels in the 1870s: in both cases colour was applied over a mid-toned brown support sufficiently thinly to allow the support to make an optical contribution. The layers of paint in the screen are not physically thin like strokes of pastel, but they are transparent nonetheless. They consist of underbound, coarsely-ground coloured pigments with rather a low refractive index, with a few very finely-ground ones of higher refractive index for toning. Only the thickest layers are fully covering. Part of the liveliness of the surface appearance is achieved simply through contrasts in paint thickness.

A thin layer of deep reddish blue paint was applied directly on top of the brown support, without any isolating or preparatory layer, for the shore, the pier and the arch of the bridge. This includes conventional Prussian blue and a coarsely-ground, transparent, copper-based pigment. The clock tower was gilded directly over the blue paint, with very yellow metal leaf that is likely to be genuine gold leaf. Application over the rough paint surface gave a textured appearance, and the gold was not burnished or polished, since this process is impossible without using the appropriate underlayers.

The greenish blue water and the sky were painted with considerable impasto, in predominantly horizontal brushstrokes, up to and over the reddish blue paint. The only vertical strokes were used to outline some design elements, and they have been gone over with horizontal strokes afterwards. There is a lot of scraping and rubbing down, exposing underlying layers and giving a mottled effect, as well as a locally applied brownish layer on top, of similar but paler tone to the support, made from umber, kaolin and chalk. There are local applications of cadmium orange, a pale chrome yellow, massicot, and red lake mixed with the blue pigments used for the shore. The moon on the right screen was completed at a late stage. It was painted with shell gold (which was, at this date a proprietary product made from genuine gold leaf powdered and made into a brushable paint), now extending over the greenish blue paint, on top of a smaller, circular moon which itself was painted as a ring of pale chrome yellow paint. There is no evidence for varnish on any of the paint or gold leaf, but some surface dirt is present.

The greenish blue water and sky areas both consist of a lighter greenish blue beneath and a darker greenish blue on top, and have a very matte texture. This paint is proteinaceous and water-based, most likely based on animal glue. Thus it is a distemper as used by decorators for special decorative effects, in interiors.

The dark shade was made predominantly from the copper-based pigment noted above, the light shade from Prussian blue and small amounts of the copper-based pigment, with quartz grains (probably acquired as fine sand) and extenders such as chalk and gypsum abundant in both layers. Some samples, generally of the lighter shade, included Mars yellow used to adjust the shade of different brush-strokes.

The copper-based pigment has not yet been successfully identified, and it could be a type of verdigris that includes sulphur and chlorine. ‘Verdigris’ could mean several materials at this date, but all of them did contain copper. Various methods of materials analysis made it clear that Whistler’s greenish blue material corresponds to none of the artists’ pigments available at the time: it more resembles a (cheaper) decorators' material, and in fact all the paint includes a lot of extenders, also indicative of cheap products.' 10

According to Walter Greaves (1846-1930), he purchased 'the verdigris blue' at 'Freeman's in Battersea' for Whistler, and this was used for the screen and for Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room y178. 11 In fact Greaves warned Whistler that the verdigris would not last. 12 What we see now as greener paint may have changed chemically, and also changed tone since Whistler applied it.

Conservation History

Professor Joyce H. Townsend comments further:

'Since the reddish-brown paper support acts as the background colour on the painted side of the screen, and the blue and green paints were not applied opaquely, all the surface colours appear less blue than they would over a white background. The paper support has grown more brown due to light exposure, making the whole tonality of the screen closer to 'green and gold' than the 'blue and gold' of the original title. The gilded elements, applied directly over the paint, are less altered from their intended colour. Dust which could have been accumulating since Whistler's time, trapped in the coarsely-textured paint, serves to dull the colours everywhere, but without shifting their tone. The colour discrepancy between the screen’s title and its present appearance would not disappear during dirt removal from the surface.' 13

In addition, she notes, 'There was no evidence for a varnish or inordinate amounts of surface dirt. Past treatment to secure flaking paint was only evident at the extreme edges.' There has been considerable damage to the paint surfaces, including abrasion and paint loss.

The screen was reconstructed at some time, and a heavy panel was infiltrated between the recto and verso. This has caused and continues to cause stress on the painted sides and on the frame. The hinges have been replaced, as have some of the nails holding the decorated panels. This also caused some damage, although it may have been necessary in order to preserve the structure. Research continues on the methods used by Whistler, and the measures taken by later conservators.

Frame

Whistler, Blue and Silver: Screen, with Old Battersea Bridge, The Hunterian

Full Screen: 195.0 x 182.0 cm. Left Screen: 195.0 x 90.3 cm. Right Screen: 195.0 x 89.6 cm.

The frame is decorated with painted nasturtiums or laurels and a series of double lines that suggest bamboo stems, and it is signed with a butterfly. Dr Joyce H. Townsend noted:

'On the frame, the flowers were painted freehand, directly over the pale white gold, which is made from metal leaf containing both gold and silver. This was cheaper than pure gold leaf, though its tone may have been an aesthetic choice. Both shades of blue distemper paint for the flowers are made from Prussian blue and lead white, a combination Whistler used often for both frame decoration and the darker blue paint in nocturnes. Here they include a lot of extenders, again suggesting a cheap material. Grains of quartz (likely pure, fine sand) provide the texture for the paint on the frame.' 14

History

Provenance

- 1879: it is not known what happened to the screen at the time of Whistler's bankruptcy.

- 1880s: the screen was deposited with Messrs Dowdeswell, London art dealers;

- 1890: returned by Charles William Dowdeswell (1832-1915) to Whistler;

- 1903: in Whistler's studio at his death and bequeathed to his ward and executrix Rosalind Birnie Philip (1873-1958);

- 1958: bequeathed by Miss R. Birnie Philip to the University of Glasgow.

According to the Pennells, whose informant was Walter Greaves (1846-1930), the screen was 'painted for Leyland but always kept for himself.' 15 Whistler's patron Frederick Richards Leyland (1832-1892) had commissioned portraits of himself and his family, but the screen is not mentioned in correspondence.

The screen was deposited with the art dealers Messrs Dowdeswell, in London, possibly when they held exhibitions of Whistler's work, in 1884 or 1886. There appears to have been a misunderstanding about the status of the deposit. When Whistler asked for it to be returned, Charles William Dowdeswell (1832-1915) wrote, on 6 December 1890:

'... as you are I believe anxious to have the screen at once, I enclose my Card for your use at your convenience I would just say that we have been under the belief that the Screen was a present in the place of a Commission on a picture sold to an American for 60 Guineas, whom Walter took down to you one day in a Cab - We are of course sorry we misunderstood the position.' 16

The chilly tone of this letter was in great contrast to the protest from Walter Dowdeswell (1858-1929) who wrote, 'What is this they write me from London about the screen? Do you want to break all our hearts? You cannot have it!' 17 Although Whistler did get it back, he appears to have been rather casual about his possessions. According to Walford Graham Robertson (1867-1948), when Whistler moved to Paris a couple of years later, he left behind 'The lovely and beloved screen that stood in the yellow dining-room' but omitted to leave his last quarter's rent or a forwarding address with the estate agents, and it was saved by the intervention of Robertson, who asked Whistler's frame maker to put it in his storeroom. 18 This story may have been exaggerated. The Whistlers left the Tower House, Tite Street, for 110 rue du Bac in 1892.

Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Little Blue Girl, Freer Gallery of Art

M. Dornac, J. McN. Whistler ... at 86 rue Notre Dame des Champs, 1890s, Freer Gallery of Art

An oil, Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Little Blue Girl y421, started in Paris in 1893/1894, includes the screen. Furthermore, a later photograph by M. Dornac shows Whistler sitting in front of the screen in Paris.

Whistler considered trying to complete Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Little Blue Girl on his return from Corsica in 1901, but the screen was still in Paris, and would have to be sent to his studio in Fitzroy Street: 'I might perhaps manage it in London - more quietly - but that would require bringing over blue screen', he told his sister-in-law. 19 Whistler closed up the studio in Paris soon afterwards and everything was returned to London at that time.

Exhibitions

- 1874: Mr Whistler's Exhibition, Flemish Gallery, 48 Pall Mall, London, 1874 (not numbered) as 'Screen – Blue and Silver'.

It was exhibited in Whistler's one-man exhibition at the Flemish Gallery in 1874 with some of the pastel studies related to the composition.

Bibliography

Catalogues Raisonnés

- Young, Andrew McLaren, Margaret F. MacDonald, Robin Spencer, and Hamish Miles, The Paintings of James McNeill Whistler, New Haven and London, 1980 (cat. no. 139), plate 114, as 'Blue and Silver: Screen, with Old Battersea Bridge', figs 395, 396.

- MacDonald, Margaret F., James McNeill Whistler. Drawings, Pastels and Watercolours. A Catalogue Raisonné, New Haven and London, 1995 (cat. nos. 480-84, 1388).

Authored by Whistler

- None.

Catalogues 1855-1905

- Mr Whistler's Exhibition, Flemish Gallery, 48 Pall Mall, London, 1874 (not numbered) as 'Screen – Blue and Silver'.

Newspapers 1855-1905

- None.

Journals 1855-1905

- Alexandre, Arsène, 'J. McNeill Whistler', Les Arts, October 1903, pp. 22-32, at p. 23, reproduces a photograph by Dornac of Whistler sitting in front of the screen in his Paris studio in rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs.

- The Studio, vol. 34, 1905, p. 223, reproduces a photograph by Dornac of Whistler sitting in front of the screen in his Paris studio in rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs.

Monographs

- None.

Books on Whistler

- Bendix, Deanna Marohn, Diabolical Designs: Paintings, Interiors, and Exhibitions of James McNeill Whistler, Washington and London, 1995, pp. 92, 94, 161, repr. fig. 38.

- Curry, David Park, James McNeill Whistler: Uneasy Pieces, New York, 2004, pp. 204, 206-07.

- Denker, Eric, In Pursuit of the Butterfly, Seattle, 1995, p. 133.

- Enaud-Lechien, Isabelle, James Whistler, le peintre et le polémiste (1834-1903), Courbevoie, 1995, p. 47.

- Getscher, Robert Harold, James Abbott McNeill Whistler Pastels, New York, 1991, p. 64.

- Lawton, Thomas, Freer: a Legacy of Art, Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, 1993, p. 171.

- Merrill, Linda, The Peacock Room. A Cultural Biography, New Haven and London, 1998, p. 182.

- Pennell, Elizabeth Robins, and Joseph Pennell, The Life of James McNeill Whistler, 2 vols, London and Philadelphia, 1908, vol. 1, p. 138.

- Pennell, Elizabeth Robins, and Joseph Pennell, The Whistler Journal, Philadelphia, 1921, pp. 122, 302.

- Petri, Grischka, Arrangement in Business: The Art Markets and the Career of James McNeill Whistler, Hildesheim, 2011, pp. 194, 283, 284.

- Spencer, Robin, The Aesthetic Movement, London and New York, 1972, pp. 76-77, repr.

- Spencer, Robin (ed.), Whistler: A Retrospective, New York, 1989, p. 83.

- Spencer, Robin, Whistler, New York, 1990, p. 72.

- Sutton, Denys, Nocturne: The Art of James McNeill Whistler, London, 1963, p. 87.

Books, General

- Ives, Colta, 'City Life', in: Colta Ives, Helen Giambruni and Sasha M. Newman (eds), Pierre Bonnard. The Graphic Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1994, pp. 110-11.

- Lambourne, Lionel, The Aesthetic Movement, London, 1996, p. 85.

- Ono, Ayako, Japonisme in Britain: Whistler, Menpes, Henry, Hornel and nineteenth-century Japan, London, 2003, pp. 74-75.

- Pyne, Kathleen A., Art and the Higher Life: Painting and Evolutionary Thought in Late Nineteenth-Century America, Austin, TX, 2010, p. 171.

- Robertson, W. Graham, Time Was: the Reminiscences of W. Graham Robertson, London and New York, 1931, pp. 199-200.

- Watanabe, Toshio, High Victorian Japonisme, Berne and New York, 1991, pp. 237, 239, 241-42.

- Whitford, Frank, Japanese Prints and Western Painters, London, 1977, pp. 143, 145 repr.

- Woodbury Adams, Janet, Decorative Folding Screens in the West from 1600 to the Present Day, London, 1982, pp. 126, 134, pl. VII.

Catalogues 1906-Present

COLLECTION:

- Hopkinson, Martin J., James McNeill Whistler at the Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, 1990, pp. 24-25, repr.

- Allan, Christopher J., A Guidebook to the Hunterian Art Gallery of the University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow, 1991, p. 14.

EXHIBITION:

- Marchant, W., Walter Greaves. Exhibition of Works, Goupil Gallery, London, 1911, p. 4 (not exhibited).

- Marchant, Wm. and Co., A Reply to an Attack Made by One of Whistler's Biographers on a Pupil of Whistler, Mr Walter Greaves and his Work, London, 1911, p. 4 (not exhibited).

- Sweet, Frederick A., James McNeill Whistler, Art Institute of Chicago and Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, Utica, 1968 (cat. no. 24) as 'Japanese Screen'.

- Spencer, Robin, James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), Nationalgalerie, Berlin, 1969 (cat. no. 25) repr. p. 39, as 'Wandschirm'.

- Young, A. McLaren, Glasgow University's Pictures, Colnaghi, London, 1973 (cat. no. 86) repr. pl. IV.

- Eitner, Lorenz and Betsy G. Fryberger, Whistler Themes & Variations, Stanford University Museum of Art, 1978, pp. 26-28 (not exhibited).

- Komanecky, Michael, 'A perfect gem', in The Folding Image: Screens by Western artists of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, 1984, pp. 58-63, 113-14 notes 77-78 (not exhibited).

- Curry, David Park, James McNeill Whistler at the Freer Gallery of Art, New York and London, 1984, p. 246, repr. fig 220.1 (not exhibited).

- Le Japonisme, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, 1988, p. 330 (not exhibited).

- The View from Afar: Whistler and the Japanese Print, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, 1988, pp. 3-4 (not exhibited).

- Dorment, Richard, and Margaret F. MacDonald, James McNeill Whistler, Tate Gallery, London, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, and National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 1994-1995, pp. 88, 130, 307 (not exhibited).

- Denker, Eric, In Pursuit of the Butterfly, Seattle, 1995, pp. 132-33, figs 5.3, 5.4 (not exhibited).

- Hobbs, Susan, The Art of Thomas Wilmer Dewing. Beauty Reconfigured, The Brooklyn Museum, 1996, p. 138, repr. fig. 17 (not exhibited).

- MacDonald, Margaret, and Patricia de Montfort, An American in London: Whistler and the Thames, Dulwich Picture Gallery, Addison Gallery of American Art, Freer Gallery of Art, 2013-2014, pp. 132-36, cat. nos. 69-71 (not exhibited).

Journals 1906-Present

- Curry, David Park, 'Whistler and Decoration', Antiques, vol. 126, no. 5, November 1984, pp. 1186-99, at pp. 1195-97, repr. fig. 13.

- Curry, David Park, 'James McNeill Whistler. Pastels ... James McNeill Whistler. A Life ...', The Burlington Magazine, vol. 136, April 1994, p. 246.

- Hackney, Stephen, 'Colour and tone in Whistler's “Nocturnes” and “Harmonies” 1871-72', The Burlington Magazine, October 1994, pp. 695-99.

- Pyne, Kathleen, 'Classical Figures, A Folding Screen by Thomas Dewing', Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts, Spring 1981, pp. 9, 15, note 27.

- Pyne, Kathleen, 'Portrait of a Collector as an Agnostic: Charles Lang Freer and Connoisseurship', The Art Bulletin, March 1996, at p. 89.

- Spencer, Robin, 'Whistler's First One-Man Exhibition Reconstructed' in: Gabriel P. Weisberg, Laurinda S. Dixon, and Antje Bultmann Lemke (eds), The Documented Image: Visions in Art History, Syracuse, New York, 1987, pp. 27-49, at pp. 32-33.

- Spencer, Robin, 'Whistler, Manet, and the Tradition of the Avant-Garde', in: Ruth Fine (ed.), James McNeill Whistler: A Reexamination, Studies in the History of Art, vol. 19, Washington, DC, 1987, pp. 47-64, at p. 54.

- Townsend, Joyce H., ‘Whistler’s Oil Painting Materials’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 136, 1994, pp. 690-95, at p. 691, fig. 37.

- Watanabe, Toshio, 'Whistler and Japan. A lecture presented to the Society on 16th October 1990', The Japan Society Proceedings, vol. 117, Spring 1991, pp. 22, 24-26.

- Watanabe, Toshio, Japan and Britain. An Aesthetic Dialogue 1850-1930, Barbican Art Gallery, London, and Setagaya Art Museum, Tokyo, 1991, p. 66.

Websites

- Hunterian website at http://collections.gla.ac.uk/#/details/ecatalogue/41285.

- ArtUK website at https://artuk.org.

Unpublished

- Revillon, Joseph Whistler, Draft Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings of J. McN. Whistler, [ca 1945-1955], Glasgow University Library (cat. no. 487).

Other

- Curry, David P., 'The Red Rag Revisited: Whistler's Decorative Watercolours', in Liana DeGirolami Cheney and Paul G. Marks (eds), The Whistler Papers, Whistler House Museum, Lowell, 1986, p. 49.

- Weber, Susan, 'Whistler as Collector, Interior Colorist and Decorator', MHPA Thesis, Cooper Hewitt Museum, New York, 1987, pp. 82-83,146 note 202, 187, fig. 75.

Notes:

1: YMSM 1980 [more] (cat. no. 139).

2: Anon., 'The Albert Bridge at Chelsea', The Times, London, 23 August 1871, p. 8.

3: Whistler to C. W. Deschamps, [20 December 1872], GUW #11438.

4: Mr Whistler's Exhibition, Flemish Gallery, 48 Pall Mall, London, 1874 (not numbered).

5: YMSM 1980 [more] (cat. no. 139).

6: Anon., 'The Albert Bridge at Chelsea', The Times, London, 23 August 1871, p. 8; anon., 'A Monster Casting', The Times, London, 23 August 1871, p. 6.

7: MacDonald, Margaret, and Patricia de Montfort, An American in London: Whistler and the Thames, Dulwich Picture Gallery, Addison Gallery of American Art, Freer Gallery of Art, 2013-2014 (cat. nos. 92-93), and see also cat. nos. 89-90 (photographs by Henry Taunt, and by York & Son).

8: The Hunterian website at http://collections.gla.ac.uk.

9: Dr Joyce H. Townsend, Senior Conservation Scientist, Tate, now Honorary Professor (History of Art), University of Glasgow; Dr Erma Hermens, University of Glasgow, now Rijksmuseum Professor of Studio Practice and Technical Art History.

10: Professor Joyce H. Townsend, report, March 2020, GUL WPP.

11: Quoted in Marchant 1911 [more], p. 4.

12: Pennell 1921C [more], p. 122.

13: Townsend, report, March 2020, op. cit.

14: Ibid.

15: Pennell 1908 [more], vol. 1, p. 138.

16: GUW #00918.

17: 7 December 1890, GUW #00919.

18: W. G. Robertson 1931 A [more], pp. 199-200.

19: Whistler to R. Birnie Philip, [8 March 1901], GUW #04797.